Reporting Highlights

- Pipeline: A Chinese prison is part of the pipeline that delivers fentanyl to the U.S., ProPublica found in a review of U.S. and Chinese documents and interviews with investigators.

- Fallout: Opioid overdoses have killed more Americans than the number of U.S. deaths in several wars combined.

- Permissive: Veteran federal agents told ProPublica that China has failed to cooperate and even interfered with drug investigations; China insists it has cracked down.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

China’s vast security apparatus shrouds itself in shadows, but the outside world has caught periodic glimpses of it behind the faded gray walls of Shijiazhuang prison in the northern province of Hebei.

Chinese media reports have shown inmates hunched over sewing machines in a garment workshop in the sprawling facility. Business leaders and Chinese Communist Party dignitaries have praised the penitentiary for exemplifying President Xi Jinping’s views on the rule of law.

But the prison has an alarming secret, U.S. congressional investigators disclosed last year. They revealed evidence showing that it is a Chinese government outpost in the trafficking pipeline that inundates the United States with fentanyl.

For at least eight years, the prison owned a chemical company called Yafeng, the hub of a group of Chinese firms and websites that sold fentanyl products to Americans, according to the U.S. congressional investigation, as well as Chinese government and corporate records obtained by ProPublica. The company’s English-language websites brazenly offered U.S. customers dangerous drugs that are illegal in both nations. Promising to smuggle illicit chemicals past U.S. and Mexican border defenses, Yafeng boasted to American clients that “100% of our shipments will clear customs.”

Although China tightly restricts the domestic manufacturing, sale and use of fentanyl products, the nation has been the world’s leading producer of fentanyl that enters the United States and remains the leading producer of chemical precursors with which Mexican cartels make the drug. Overdoses on synthetic opioid drugs, most of them fentanyl related, have killed over 450,000 Americans during the past decade — more than the U.S. deaths in the Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined.

The involvement of a state-run prison is just one sign of the Chinese government’s role in fomenting the U.S. fentanyl crisis, U.S. investigators say. Chinese leaders have insistently denied such allegations. But U.S. national security officials said the Yafeng case shows how China allows its chemical industry to engage openly in sales to overseas customers while blocking online domestic access and enforcing stern laws against drug dealing inside the country. Beijing also encourages the manufacture and export of fentanyl products, including drugs outlawed in China, with generous financial incentives, according to a bipartisan inquiry last year by the House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party.

“So the Chinese government pays you to send drugs to America but executes you for selling them in China,” Matt Cronin, a former federal prosecutor who led the House inquiry, said in an interview. “It’s impossible that the Chinese Communist Party doesn’t know what’s going on and can’t do anything about it.”

China’s antidrug cooperation has been persistently poor, U.S. officials said. In 2019, Xi imposed controls that cut the export of fentanyl, but Chinese sellers shifted to shipping precursors to Mexico, where the cartels expanded their production.

“We couldn’t get the Chinese on the phone to talk about fighting child pornography, let alone fentanyl,’’ said Jacob Braun, who served as a senior official at the Department of Homeland Security during the Biden administration. “There was zero cooperation.”

China also remains the base of global organized crime groups that launder billions for fentanyl traffickers in the U.S, Mexico and Canada. ProPublica has previously reported that this underground banking system depends on the Chinese elite, who move fortunes abroad by acquiring drug cash from Chinese criminal brokers for Mexican cartels. Chinese banks and businesses also help hide the origin of illicit proceeds. The regime in Beijing therefore has considerable control over key nodes in the fentanyl chain: raw materials, production, sales and money laundering.

U.S. leaders, Democrats and Republicans alike, have accused China of using fentanyl to weaken the United States. Some veteran agents agree.

Ray Donovan, who retired in 2023 as the Drug Enforcement Administration’s chief of operations, said he believes that a “deliberate strategy” by the Chinese state has caused the trafficking onslaught “to grow in size and scope.”

“They have said for years that they are cracking down,” Donovan said in an interview. “But we haven’t seen meaningful action.”

Still, current and former U.S. officials told ProPublica that the national security community has not found conclusive evidence of a planned, high-level campaign against Americans by the Chinese government. That is partly because for years the U.S. treated fentanyl as a law enforcement matter rather than a national security threat, making it hard to gather intelligence about the extent and nature of the regime’s role.

“If this was Chinese intelligence doing something, we have a focus on that as counterintelligence,” said Alan Kohler, who retired from the FBI in 2023 after serving as director of the counterintelligence division. “If it was drug cartels, we have a criminal focus on that. But this area of crime and state converging falls between the seams in and among agencies.”

Nonetheless, the current and former officials said rampant fentanyl trafficking could not continue without at least the passive complicity of the world’s most powerful police state.

“I haven’t seen smoking-gun evidence that it’s a policy or strategy of the government at a high level,” Kohler said. “You could argue that their decision not to do anything about it, even after the results are clear, is tacit support.”

In a written statement, the spokesperson for China’s embassy in Washington described as “totally groundless” any allegation that the regime has fomented the crisis.

“The fentanyl issue is the U.S.’s own problem,” said the spokesperson, Liu Pengyu. “China has given support to the U.S.’s response to the fentanyl issue in the spirit of humanity.” At the United States’ request, he said, China in 2019 restricted “fentanyl-related substances as a class,” becoming the first country to do so, and has cooperated with the U.S. on counternarcotics.

“The remarkable progress is there for all to see.”

The Trump administration has made the fight against fentanyl a priority and in February imposed a 25% tariff on Chinese imports to pressure Beijing for results. The approach could put a dent in the drug trade, but it’s too early to tell, officials said.

“The Chinese system responds to a negative incentive,” said former FBI agent Holden Triplett, who served as legal attache in Beijing and director of counterintelligence on the National Security Council. “China may be willing to endure more pain than we can give. But it is our only chance.”

To respond effectively, the U.S. needs a clearer picture of the Chinese fentanyl underworld, Triplett and others say. The activities of the Shijiazhuang prison are a compelling case study, but not the only one.

To examine the role of the Chinese state in the drug trade, ProPublica interviewed more than three dozen current and former national security officials for the U.S. and other countries, some of whom provided exclusive inside accounts. The reporting also drew on last year’s House investigation, digging into significant findings that have received little public attention, plus court files, government documents, academic studies, private inquiries and public records in the U.S., China and Mexico.

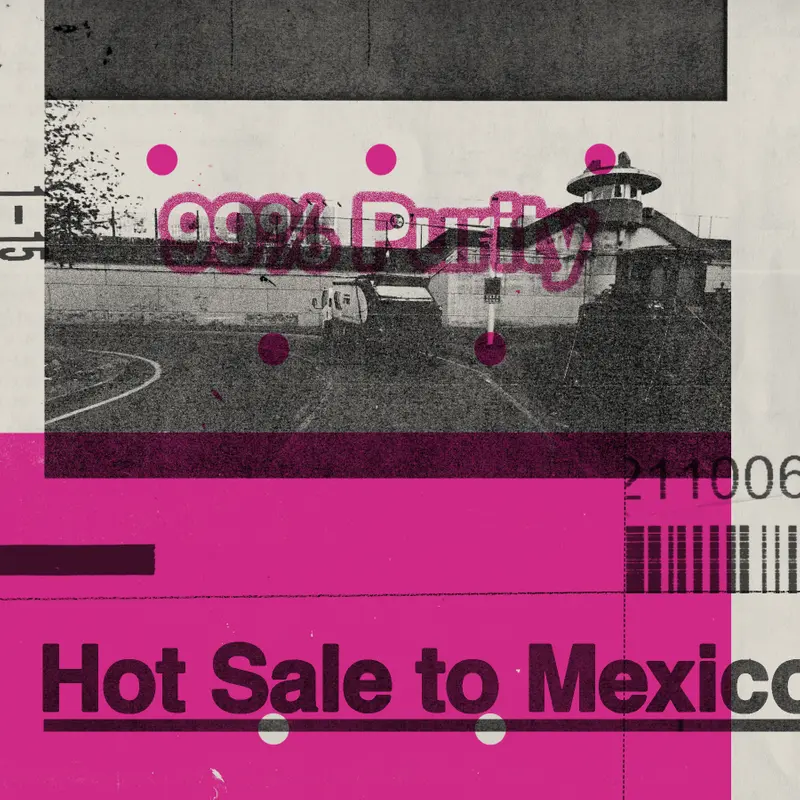

Credit:

Collage by Mike McQuade for ProPublica. Source images: Google Maps and screenshots from ads found by a U.S. congressional inquiry.

Prison Business

In 2010, the Hebei Prison Administration Bureau combined three detention facilities to create a high-security prison in Shijiazhuang, the capital of Hebei province. The region is a base of China’s chemical industry, which is the largest in the world. It is also weakly regulated and freewheeling, according to U.S. national security officials, private studies and other sources. A shifting array of companies peddle everything from innocuous fertilizers to deadly opioids.

Liu Jianhua, a veteran Chinese Communist Party official with a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Illinois Chicago, became director of the prison in 2014. By then, fentanyl was cutting a swath across America. Overdose deaths soared due to the ease with which U.S. users and dealers could acquire fentanyl products by mail from China.

China’s high-tech surveillance apparatus aggressively polices the online activities of its citizens. Yet sales of fentanyl to foreigners have thrived on popular, easily accessible websites, said Frank Montoya Jr., a former FBI agent with years of China-related experience who served as a top U.S. counterintelligence official.

“You don’t have to go on the dark web,” Montoya said. “It is out in the open.”

Yafeng Biological Technology Co. Ltd., also known as Hebei Shijiazhuang Yafeng Chemical Plant, became a typical player on this frontier, the congressional inquiry found. (As part of its reporting, ProPublica mapped links between the prison, the company and the U.S. drug market with the help of two entities that specialize in China open-source research: Sayari, a company that provides risk management and supply-chain analysis and that supported the House inquiry, and C4ADS, a nonprofit that investigates illicit global networks.)

Yafeng’s websites and Chinese corporate records describe the firm as a chemical manufacturer. It has ties through other websites, phone numbers and email addresses to at least nine companies that advertised illicit drugs, causing investigators to conclude that Yafeng was a network hub, according to the report and interviews. It’s common for interconnected Chinese fentanyl producers and brokers to obscure details about their enterprises and change names and platforms to elude detection, U.S. officials said.

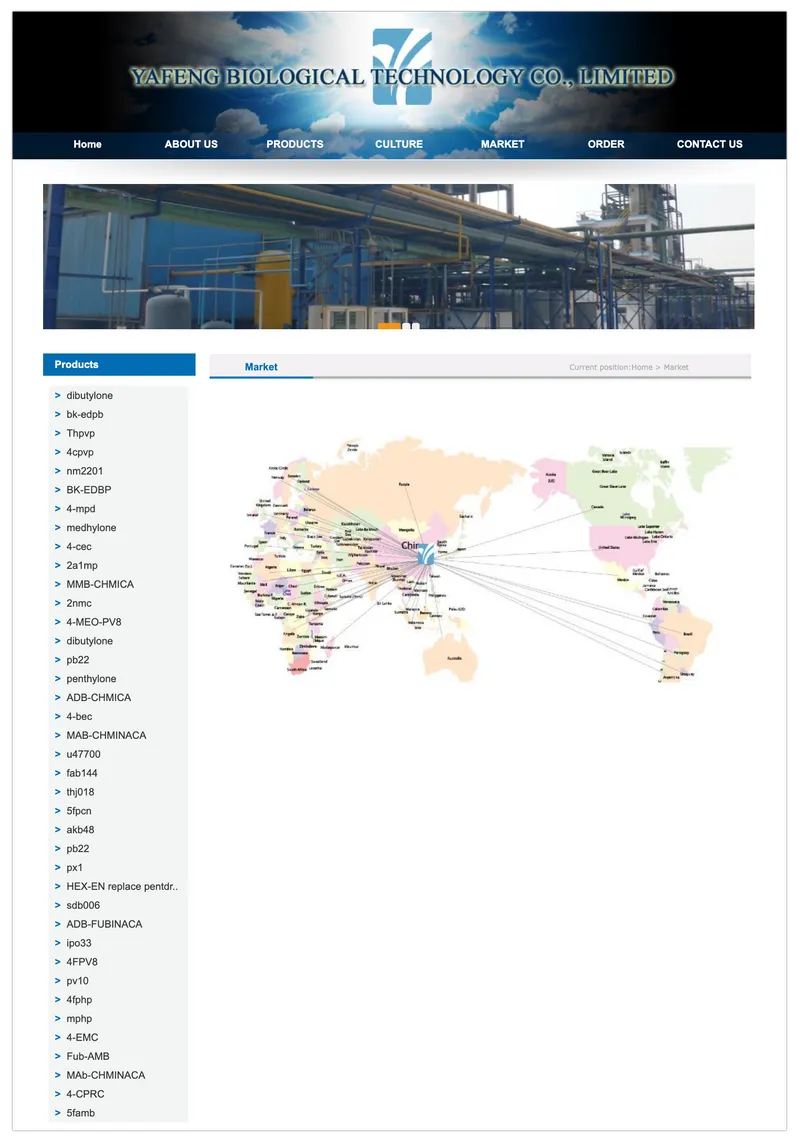

In some ways, Yafeng presented itself to foreign buyers as a respectable company. The English-language websites featured peppy phrases like “team spirit” and “promoting the well-being of community.” The China-based sales representatives gave themselves Western names: Diana, Monica, Jessica. A map of markets showed shipping routes from China to the United States, Mexico, Canada and other countries.

Credit:

U.S. government

Yet the sales pitches left little doubt that the firm knew its activities were illegal. Yafeng websites utilized familiar terms assuring U.S. and Mexican drug users and traffickers of the company’s skill at smuggling illegal narcotics overseas, according to the House report and U.S. investigators. The company touted its use of “hidden food bags,” a method in which drugs are concealed in shipments labeled as food products. Ads promised “strong safety delivery to Mexico, USA” with “packaging made to measure” to “guarantee” that illicit chemicals would elude border inspections, documents show.

Credit:

U.S. government

Chinese traffickers often discuss lawbreaking in such brazen terms with foreign customers, seemingly unconcerned about China’s omnipresent surveillance system, court files and interviews show. Another firm, Hubei Amarvel Biotech, explicitly explained to U.S. and Mexican clients online — complete with photos — its methods for “100% stealth shipping” of drugs disguised as nuts, dog food and motor oil, court documents say. After undercover DEA agents lured two Amarvel executives to Fiji and arrested them, a New York jury convicted them in February on charges of importation of fentanyl precursors and money laundering. (One defendant, Yiyi Chen, has filed a motion requesting an acquittal or retrial.)

At the time of the arrests, the Chinese government issued a statement condemning the U.S. prosecution as “a typical example of arbitrary detention and unilateral sanctions.”

Similarly, Yafeng websites displayed photos of narcotics in plastic baggies to peddle a long list of chemicals, including fentanyl precursors and U-47700, a powerful fentanyl analogue outlawed in both the U.S. and China that has no medical use, the House report says.

One victim of U-47700 was Garrett Holman of Lynchburg, Virginia. Holman had fallen in with youths who discovered how easy it was to buy synthetic drugs online. In late 2016, Holman overdosed on U-47700, street name “pinky,” that arrived by mail from southern China. His father, Don, performed CPR before paramedics rushed Holman to the hospital. Although he survived, another overdose killed him just days before his 21st birthday in February 2017.

Credit:

U.S. government

“My son’s opioid exposure was less than two months,” Don Holman told a hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Committee the next year. “At 20 years old, I do not believe my son deserved to die for his initial bad choices.”

The father handed over evidence, including the envelope in which the drugs arrived, to federal agents, who traced about 20 shipments back to the same sender in China, he said in an interview. Don Holman blames the fentanyl crisis on the American appetite for opioids as well as the Chinese government. He has spent eight years telling anyone he can, from drug czars to fellow parents, about the experience that shattered his family.

“I’ve had to hit parents right between the eyes, like: ‘Hey, your child is not going to be here if you don’t do something,” he said. “You need to wake up.’”

No link to Yafeng surfaced in that case. The firm’s sales of U-47700 and other illicit drugs occurred during a period when its sole owner and controlling shareholder was the Shijiazhuang prison, according to the House inquiry, Sayari and C4ADS.

One of Yafeng’s street addresses was that of the prison, ProPublica determined through satellite photos and public records. Another Yafeng address next door also houses the offices of a clothing firm owned by the provincial prison administration. A third Yafeng address a few blocks away is a former municipal police station, records and photos show.

The director of the prison, Liu Jianhua, left his post after becoming the target of a corruption inquiry in 2021, according to Chinese media reports. It’s unknown how that investigation was resolved or if his fall had anything to do with the drug activity. Liu could not be reached for comment. The prison administration did not respond to requests for comment.

Yafeng stopped doing business under that name at some point between 2018 and 2022, records show. Yet the Yafeng group continued to function through at least one of its affiliated websites, protonitazene.com, the congressional report said. As of last year, the site was still advertising “hot sale to Mexico” of drugs including nitazenes, which are 25 times more powerful than fentanyl.

Government Incentives

Yafeng is not the only company with connections to the Chinese state and fentanyl.

Gaosheng Biotechnology in Shanghai is “wholly state-owned,” congressional investigators found. The company sold fentanyl precursors and other narcotics — some illegal in China — on 98 websites to U.S., Mexican and European customers, the report says. Senior provincial development officials visited Gaosheng and praised its benefits for the regional economy. Gaosheng did not respond to requests for comment.

The Chinese government owned a stake in Zhejiang Netsun, a private firm that had a Chinese Communist Party member serving on its board of directors as a deputy general manager, the congressional report says. Netsun carried out over 400 sales of illegal narcotics, the report says, and served as a billing or technical contact for over 100 similar companies — including Yafeng. Netsun did not respond to requests for comment.

And the Shanghai government gave monetary awards and export credits to Shanghai Ruizheng Chemical Technology Co., a “notorious seller of fentanyl products, which it advertises widely and openly on Chinese websites like Alibaba,” the report says. Chinese officials invited company reps to roundtable discussions about technology and business. Shanghai Ruizheng did not respond to requests for comment.

Chinese government officials who interact with the trafficking underworld are often prominent in provincial governments, where corruption is widespread, said a former senior DEA official, Donald Im, who led investigations focused on China. Not only can they make money through kickbacks or investments, but they benefit politically, rising in the Communist Party hierarchy if their local chemical industries prosper.

“Key government officials know about the fentanyl trade and they let it happen,” Im said.

China’s central government also plays a vital role by providing systemic financial incentives that fuel fentanyl trafficking to the Americas, U.S. officials say. The House inquiry discovered a national Value-Added Tax rebate program that has spurred exports of at least 17 illegal narcotics with no legitimate purpose. They include a fentanyl product that is “up to 6,000 times stronger than morphine,” the House report says.

This state subsidy program has pumped billions of dollars into the export of fentanyl products, including ones outlawed in China, according to the report and U.S. officials. The tax rebate is 13%, the highest available rate. To qualify, companies have to document the names and quantities of chemicals and other details of transactions, the report says.

The existence of this paper trail refutes a frequent claim by Chinese leaders: that weak regulation of the chemical sector makes it impossible to identify and punish suspects.

Chinese officials did not respond to specific questions about the government financial incentives or the state-connected companies involved in drug trafficking. But the embassy spokesperson said China has targeted online sellers with a “national internet cleanup campaign.”

During that crackdown, Liu Pengyu said, Chinese authorities have cleaned “14 online platforms, canceled over 330 company accounts, shut down over 1,000 online shops, removed over 152,000 online advertisements, and closed 10 botnet websites.” He said Chinese law enforcement has determined that many illegal ads appear on foreign online platforms.

Wall of Resistance

In May 2018, Cronin — then a federal prosecutor based in Cleveland — went to Beijing in pursuit of one of the biggest targets in the grim history of the fentanyl crisis: the Zheng drug trafficking organization, an international empire accused of trafficking in 37 U.S. states.

Cronin and his team of agents hoped to persuade Chinese authorities to prosecute Guanghua and Fujing Zheng, a father and son who were the top suspects. They ran into a wall of resistance.

In an interview, Cronin recalled walking into a cavernous room in China’s Ministry of Public Security where a row of senior officials and uniformed police waited at a long table. A curtain-sized Chinese flag covered a wall.

Cronin took a breath, opened a stack of binders he had lugged from Cleveland and presented his case. The prosecutor laid out evidence connecting the Zhengs, who were chemical company executives based in Shanghai, to two overdoses in Ohio. The U.S. distribution hub was a warehouse near Boston run by a Chinese chemist, Bin Wang. Later, Wang said he simultaneously worked for the Chinese government “tracking chemicals produced in China” and traveled home monthly from Boston “to consult with Chinese officials,” a memo by his lawyer said.

The response of the Chinese counterdrug chiefs was a brush-off, Cronin recalled in the interview. Essentially, he said, they told him: “You are right that the Zhengs are exporting these drugs that are killing Americans. But unfortunately, technically what they are doing is not a violation of Chinese law.”

Cronin pulled out another binder. He went over evidence and an expert analysis showing that the Zhengs had committed Chinese felonies, including money laundering, manufacturing of counterfeit drugs and mislabeling of packages.

Tensions rose when the Chinese officials responded that, unfortunately, the police unit that handled such offenses was not available; they rebuffed Cronin’s offer to delay his return flight in order to meet with that unit, he said.

After the U.S. Justice Department charged the Zhengs that August with a drug trafficking conspiracy resulting in death, a Chinese newspaper reported that a Chinese senior counterdrug official criticized the case. The U.S. “failed to provide China any evidence to prove Zheng violated Chinese law,” the official said.

Credit:

Courtesy of James Rauh

Later, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned the Zhengs and designated the son as a drug kingpin. U.S. investigators told ProPublica they concluded that the Zhengs operated with the blessing of the Chinese government, citing the defendants’ sheer volume of business, high-profile online activity and open communications on WeChat, the Chinese messaging platform that authorities heavily monitor.

Ohio courts granted millions of dollars in civil damages to the family of Thomas Rauh, a 37-year-old who died of an overdose in Akron in 2015. The family never received any money, however.

Rauh’s father, James, who traveled and did business in China in his youth, has become an antidrug activist. He said the U.S. government must do more to crack down on China’s role and counter public stigma that still blames addicts.

“I don’t think the U.S. government wants to take the responsibility for confronting this,” he said.

A decade of frustration has compelled James Rauh to call for a drastic solution. He wants the U.S. to designate fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction in response to what he sees as an intentional Chinese campaign.

“It’s asymmetric warfare,” he said.

The Zhengs remain free in China and have never responded to the allegations in court. During a brief encounter with a “60 Minutes” journalist in Shanghai in 2019, Guanghua Zheng denied he was still selling fentanyl in the United States and said the Chinese government “has nothing to do with it.” Wang pleaded guilty and served prison time.

The Zheng case is typical, said Im, the former senior DEA official. Thousands of DEA leads relayed to Chinese counterparts over the years have been “met with silence,” he said. In other cases, Chinese officials have asked for more details about the targets of U.S. investigations — and then warned suspects linked to the Communist Party, Im said.

Most U.S. national security officials interviewed for this story described similar experiences, citing a few exceptions, such as a joint U.S.-Chinese operation in Hebei province in 2019.

A former DEA agent, William Kinghorn, recalled the dispiriting aftermath of an investigation he oversaw centered on Chuen Fat Yip, whose firms allegedly distributed more than $280 million worth of drugs. Yip has denied wrongdoing and denounced U.S. criminal charges and sanctions. He is on the DEA’s 10 most wanted fugitives list and remains free in China, U.S. officials said.

“We obtained information that the Chinese authorities did ban or shut down the companies” the DEA targeted in the case, Kinghorn said in an interview. “We learned that afterward these same people [linked to Yip] were now owning or managing similar companies. Even though they had been banned, they basically just changed the name of the company.”

A sense of impunity persists in the chemical industry, according to a 2023 inquiry by Elliptic, a U.K. analytics firm. It reported that many of the 90 Chinese companies contacted by its undercover researchers were “willing to supply fentanyl itself, despite this being banned in China since 2019.”

The final year of the Biden administration brought signs of modest progress in China, including new regulations, shutdowns of firms, and arrests of a suspected money launderer and four senior chemical company employees charged by U.S. prosecutors.

Citing those cases from 2024, spokesperson Liu Pengyu said China has “collaborated closely” with the U.S., adding, “Multiple major cases are making great progress.”

Meanwhile, U.S. overdose deaths fell by 33% compared with the previous year, according to the annual threat assessment by the U.S. intelligence community released March 25. The drop may be tied to the increased availability of naloxone, a drug for treating overdoses, the report said.

The threat assessment report warned that “China likely will struggle to sufficiently constrain” companies and criminal groups involved in the U.S. fentanyl trade, “absent greater law enforcement actions.”

Cronin, the former federal prosecutor, went on to become chief investigative counsel for the House Select Committee. He led last year’s inquiry into China’s role in the fentanyl crisis. The committee’s review of seven Chinese company websites found over 31,000 instances of firms offering illegal chemicals during a period of about three months in early 2024.

Undercover communications with the firms “revealed an eagerness to engage in clearly illicit drug sales,” the report says, “with no fear of reprisal.”

Kirsten Berg contributed research.