The question was a simple one: Had Nike, the athletic apparel brand dogged by sweatshop allegations more than two decades ago, truly become a beacon of environmental stewardship and fair labor practices, as it claimed?

As editor for ProPublica’s Northwest team and a longtime Oregonian, I was as eager to know the answer as the Portland-based reporter who posed the question, Rob Davis.

Nike is woven into Oregon’s fabric. It’s one of the Portland area’s largest employers and one of the state’s few Fortune 500 companies. Nike’s headquarters in the Portland suburbs is a 400-acre complex of buildings, running paths and sports fields where fashion design and athleticism meet. At the University of Oregon, alma mater of Nike co-founder Phil Knight, buildings across the campus bear his name or the names of his relatives.

The trouble was that the answer to Davis’ question primarily lay across the Pacific Ocean. Although ProPublica is undaunted by stories that take time and, yes, money — see recent reporting by reporters Josh Kaplan and Brett Murphy from Gambia, for example — Davis first needed to prove to editors that an overseas trip would bring us a story that broke new ground.

One of our most important decisions early on was to partner with reporter Matthew Kish and his editors at The Oregonian/OregonLive, where Davis and I worked previously. Kish has covered Nike for more than a decade and knows the company as well as perhaps any reporter in the country.

Kish and Davis started reviewing public reports that Nike had put out over the past two decades and every news article they could find about the company’s efforts in the realm of social responsibility. Davis spoke by phone with labor advocates around the globe. He even found a few factory workers in Asia willing to talk in late-night (for them) video calls about their working conditions.

The nut that Davis and Kish couldn’t crack was Nike itself. The reporters told Nike’s public relations team about their interest. Might Nike staffers share what they were finding in factory audits or how they were ensuring compliance with Nike’s code of conduct? The PR people at various points provided some background information, including excerpts of past corporate reports, but the company chose not to make anyone available for on-the-record interviews at that stage.

(I also asked Nike last week to weigh in on the company’s interactions with Kish and Davis or about the stories they’ve written for this series; a Nike spokesperson declined to comment to me on the record.)

With layoffs hitting Nike last year, Kish and Davis had an opening to talk with insiders about one particular aspect of the company’s social responsibility efforts. Pursuing a tip, the two worked with research reporter Alex Mierjeski to compile a list of employees who had worked in sustainability roles. The reporters started knocking on virtual doors: about 100 of them. They established that Nike’s reorganization had taken a heavy toll on the workforce whose efforts included reducing the company’s carbon footprint.

This time, Nike responded by granting an interview with its chief sustainability officer, the only interview the company has given for this project to date during more than a year of reporting. It lasted 17 minutes. She said the company remained committed to sustainability and described its strategy as “embedding” the work throughout the company.

We published stories laying out the departures and one other development that seemed to go against Nike’s declared intent to help the planet: increasing emissions from its private jets.

Yet something remained missing from our reporting. The former sustainability workers spoke English. Many were based in Oregon. They had online presences. Understanding working conditions in Nike’s factories called for gaining a closer vantage point on the company’s far-flung foreign supply chain.

Davis zeroed in on one specific claim from Nike. The company has said that the factories for which it has data pay their workers, on average, 1.9 times the local minimum wage. It provided no breakdown of factories included in the calculation, and it wasn’t clear how widely pay might vary from the average. So Davis started requesting paystubs for workers across the globe. We hoped that even scattered data would help us test Nike’s math.

Paystubs trickled in. A handful of workers from a factory in Central America. More from Indonesia. A smattering from Cambodia.

Then, a breakthrough.

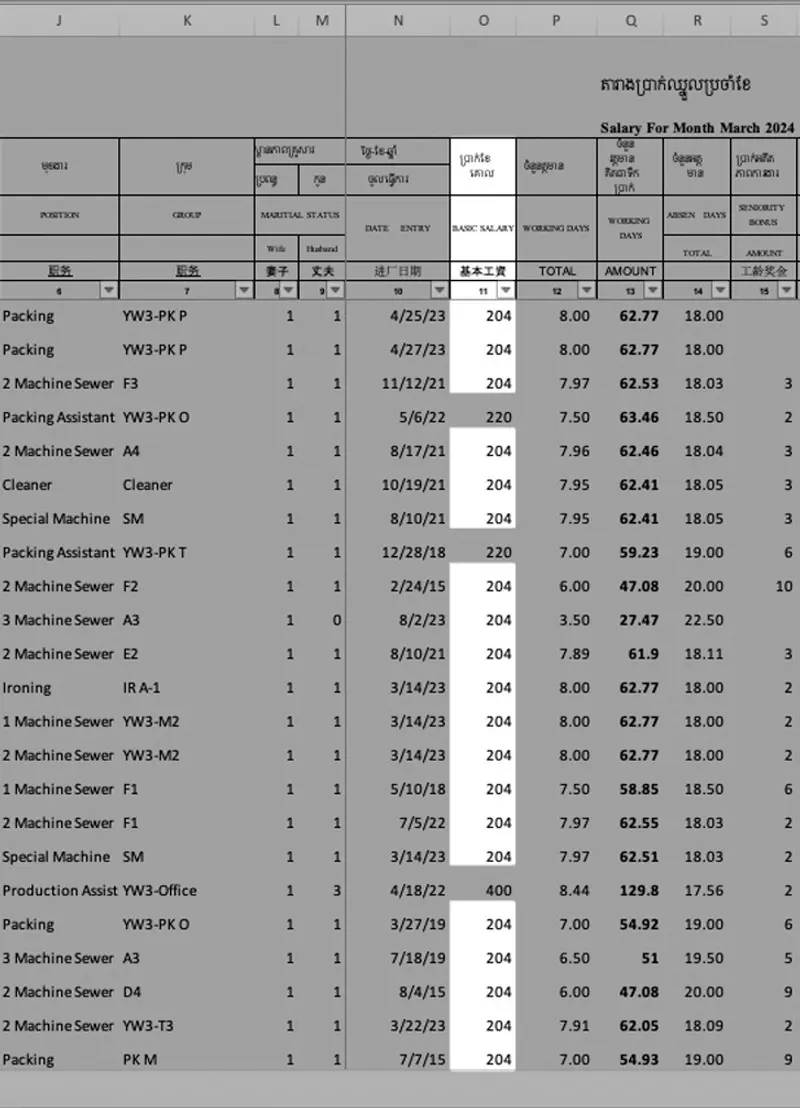

Davis received an Excel spreadsheet in English and Khmer, the language most widely spoken in Cambodia. It was a payroll ledger for Y&W Garment, which made baby clothing for Nike from 2022 to 2023. Davis could see every employee’s job title, age, hiring date, gender and pay amounts.

This was one factory in a supply chain made up of hundreds, 3,720 workers out of more than 1.1 million that Nike’s suppliers employ globally. But it was a uniquely comprehensive window. Quick calculations showed that only a tiny share of Y&W’s workforce — just 1% — made 1.9 times the minimum wage, the amount that Nike said was typical.

Credit:

Obtained by ProPublica. Highlights and redactions by ProPublica.

Davis connected with a bilingual freelance journalist in Phnom Penh, Keat Soriththeavy, who tracked down some of the workers named in the payroll ledger. Now we had factory sources on the ground. We had someone to help Davis translate what they had to say. And we had our spreadsheet. I told Davis to book a ticket for January.

On a Sunday morning, less than a day after his plane landed in Cambodia’s capital, Davis met a group of workers on their only day off. After introductions through our hired translator, Davis pulled an iPad out of his travel bag and passed it around, asking whether the details of the digital payroll ledger were accurate.

One by one, each worker studied the entry by their name. “Correct?” Davis asked. Pause for translation.

“Yes.”

Around the table they went: Correct. Yes. Correct.

Credit:

Rob Davis/ProPublica

Davis spent the rest of his 12-day visit traveling by tuk-tuk — a tiny three-wheeled taxi named for its puttering engine — to meet workers in small villages around Phnom Penh. Cambodian garment workers are typically on the clock at least six days a week, leaving limited free time to spend with family or a visiting journalist. Yet with Keat’s help, Davis managed to talk with a total of 14, some willing to be identified by name. They told him the money they made in a 48-hour work week wasn’t enough to live on and that they needed overtime to make ends meet.

Credit:

First image: Keat Soriththeavy. Second image: Rob Davis/ProPublica

When workers began telling Davis that people fainted in the hot factory and needed to be treated at its clinic, he messaged me to gauge my reaction. I asked: Could he find a doctor who treated them? Very quickly, Davis got a phone number for a clinic staffer willing to talk. The medical worker helped us quantify the scale of the problem, telling Davis as many as 15 people a month became too weak to work in the hot months of May and June. (As used in Cambodia, the term “fainted” can describe becoming too weak to work.)

ProPublica photojournalist Sarahbeth Maney followed on Davis’ trail a month later. She documented, with intimate portraiture, the home life of people from a factory where base pay started at about $1 per hour.

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica

Nike did not answer detailed questions from Davis about wages or faintings, instead issuing a written statement. The company said it is “committed to ethical and responsible manufacturing” and that it expects suppliers “to continue making progress on fair compensation for a regular work week.”

Representatives of Y&W Garment and its Hong Kong parent, Wing Luen Knitting Factory Ltd., did not respond to Davis’ emails, text messages or phone calls. Haddad Brands, which Y&W workers told Davis served as an intermediary for Nike at the Phnom Penh facility, didn’t respond to emails asking about conditions there.

As Davis was drafting his story, President Donald Trump’s plan to raise tariffs on goods manufactured overseas sent Nike’s stock prices tumbling. One declared goal was to reverse the economic forces that drove Nike and others to make their products in places like Cambodia and not the U.S. It seemed, honestly, like Nike’s track record in the region might be losing relevance.

But experts told Davis and Kish, our reporting partner at The Oregonian, quite the opposite. Rather than bring jobs home, brands might simply squeeze their foreign suppliers for greater productivity.

It made the issues that drove Davis from the beginning as pressing as they have ever been. Had Nike lived up to its promises in Southeast Asia?

At one Cambodian factory, Davis’ tenacity brought us a simple answer: No.

Credit:

Sarahbeth Maney/ProPublica